Risk Comparison Calculator

Input Your Risk Data

Why This Matters

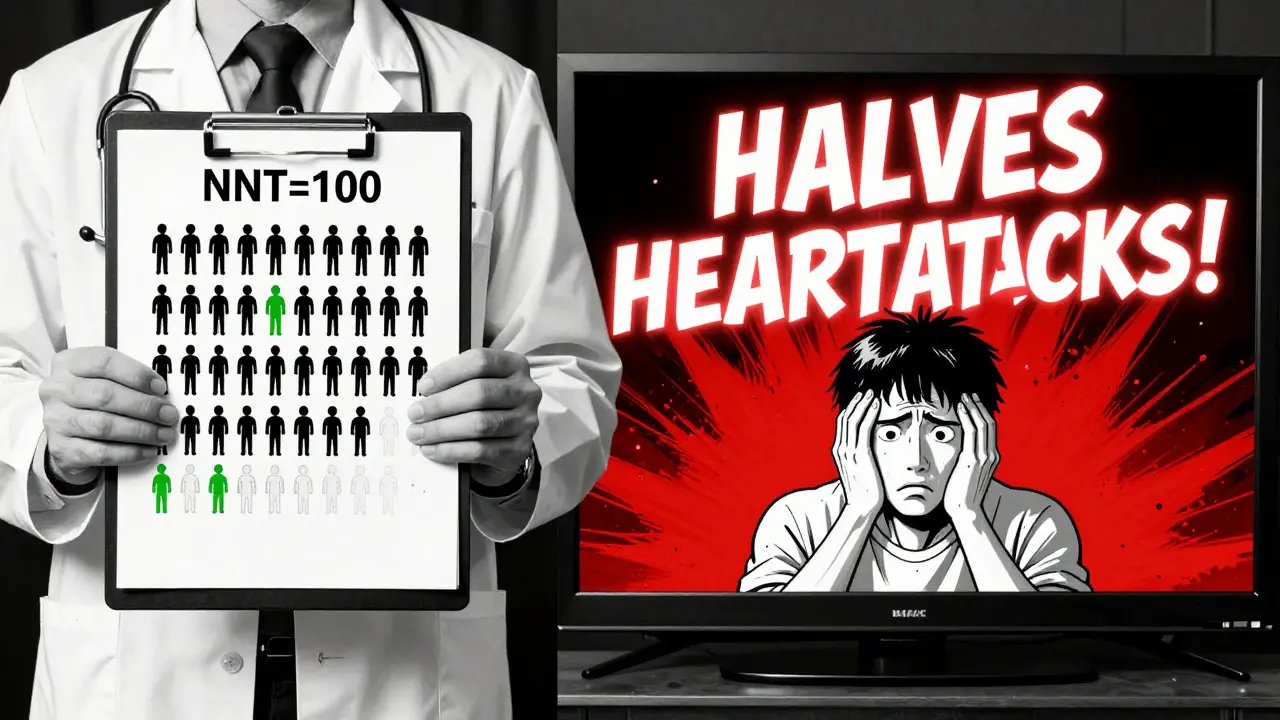

Number Needed to Treat (NNT) tells you how many people need treatment to prevent one bad outcome. Example: NNT = 100 means 100 people must take the drug for one person to benefit.

Risk Comparison Results

Enter your baseline and treatment risk values above to see the comparison.

Imagine this: You’re handed a brochure saying a new drug reduces your risk of a heart attack by 50%. That sounds amazing - until you find out your original risk was only 2%. The drug brings it down to 1%. That’s not a miracle. It’s a 1 percentage point change. This is the gap between absolute risk and relative risk, and it’s the reason so many people misunderstand how drugs really affect them.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk tells you the actual chance of something happening to you. It’s simple: out of 100 people like you, how many will experience the side effect or benefit? If 1 in 1,000 people on a drug get a rare liver problem, that’s an absolute risk of 0.1%. If 10 in 100 get nausea, that’s 10%. These numbers don’t lie. They’re grounded in real people, real outcomes.Doctors use absolute risk to decide if a treatment’s benefit is worth the cost. For example, if a statin reduces heart attacks from 4% to 3% in a group of 100 people, the absolute risk reduction is just 1%. That means 100 people need to take the drug for one person to avoid a heart attack. That’s the Number Needed to Treat - or NNT - and it’s 100 in this case. That’s not a small number. It tells you the drug helps, but not for everyone.

When side effects are reported as absolute risk, you get the truth. If 15 out of 100 people on a certain antidepressant report sexual problems, that’s a 15% chance. No spin. No math tricks. Just facts. This is what matters when you’re deciding whether to start a medication.

How Relative Risk Can Be Misleading

Relative risk compares two groups: those who took the drug and those who didn’t. It’s a ratio. If your risk of a side effect is 2% without the drug and 4% with it, the relative risk is 2.0 - meaning you’re twice as likely to have it. That sounds scary. But look closer: going from 2% to 4% is only a 2 percentage point increase. In absolute terms, 98 out of 100 people still won’t have the side effect.Pharmaceutical ads love relative risk because it makes small changes look huge. A drug that cuts your stroke risk from 0.2% to 0.1% sounds like it’s cutting it in half - 50% relative risk reduction. But in reality, you’re going from 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000. That’s a 0.1 percentage point change. For most people, that’s not life-changing. It’s barely noticeable.

Here’s the problem: relative risk doesn’t tell you where you started. A 90% reduction in risk sounds impressive - until you learn the original risk was 0.001%. That’s like saying you reduced your chance of being struck by lightning from 1 in a million to 1 in 10 million. The math checks out, but the impact? Nearly zero.

Why Both Numbers Matter - Together

Neither absolute nor relative risk tells the whole story alone. You need both. Absolute risk tells you how likely something is to happen to you. Relative risk tells you how much the drug changes that chance compared to not taking it.Take venlafaxine, an antidepressant. Studies show 20% of people on it get sexual side effects. On placebo, it’s 8.3%. The relative risk is 2.41 - meaning you’re more than twice as likely to have this side effect. But the absolute difference? Just 11.7 percentage points. So, for every 10 people who take it, about 1 or 2 will experience this side effect that they wouldn’t have otherwise. That’s useful context.

Doctors who use both numbers help patients make better decisions. One patient told me she refused a blood pressure drug because the ad said it "reduced heart attack risk by 30%" - she thought it meant 3 out of 10 people would be saved. When I showed her her baseline risk was 3%, and the drug lowered it to 2.1%, she understood: it helped, but not dramatically. She agreed to try it, knowing what to expect.

How the Industry Uses This Against You

The pharmaceutical industry isn’t trying to trick you - at least, not always. But they know what numbers work. Ads focus on relative risk because it’s bigger, flashier, and more persuasive. A 50% reduction sounds better than a 1% reduction, even when they’re talking about the same thing.A 2021 study found that 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. only showed relative risk. Only 12% mentioned absolute risk. And fewer than 5% gave the Number Needed to Treat. That’s not transparency. That’s marketing.

Even worse, they rarely mention time frames. "Reduces heart attack risk by 40%" - over 5 years? 10 years? A year? That changes everything. A 40% reduction over 10 years is very different from a 40% reduction over 12 months.

And then there’s side effects. Ads often downplay them by using absolute numbers - "only 5% of users report headaches." But if the placebo group had 2%, that’s a 150% increase in relative risk. The ad doesn’t say that. Why? Because it makes the drug look worse.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

You don’t need to be a statistician to understand your risks. Just ask the right questions:- "What’s my risk of this problem without the drug?"

- "What’s my risk with the drug?"

- "How many people like me need to take this for one person to benefit?"

- "What’s the chance I’ll have a side effect that I wouldn’t have had otherwise?"

Don’t accept answers like "It reduces risk by half" or "It’s very safe." Push for numbers. If your doctor doesn’t have them handy, ask for a printed patient leaflet - those are required to include both absolute and relative risks in Europe, and often in the U.S. too.

Visual tools help. Some clinics use "risk ladders" - pictures of 100 people, with some colored in to show who gets the benefit or side effect. One red dot for the side effect. Three green dots for the benefit. Suddenly, the trade-off is clear.

Real People, Real Confusion

This isn’t theoretical. People get it wrong - even doctors.A 2019 study found that 60% of surveyed physicians couldn’t convert a relative risk reduction into absolute terms. That means a lot of doctors are giving patients incomplete information.

On Reddit, one patient wrote: "I refused statins because I thought it meant half the people wouldn’t have heart attacks. I didn’t realize my risk was only 2% to begin with." Another said: "The ad said 50% fewer heart attacks. I thought I’d have a 50% chance of avoiding one. I felt stupid when I found out it was 2% to 1%."

That’s the cost of poor communication. People skip meds they could benefit from. Or they take drugs they don’t need, scared by inflated numbers.

What’s Changing - and What’s Not

There’s hope. In 2023, the FDA released draft rules pushing for clearer risk reporting in drug ads. The Cochrane Collaboration now gives doctors templates to explain risks using both numbers. Harvard Medical School now teaches this in its curriculum.But change is slow. The market for drugs is worth over $1.5 trillion. Companies still rely on relative risk to drive prescriptions. And patients? They’re still being sold fear and hope - not facts.

The good news? You don’t need to wait for regulators to fix this. You can ask for the numbers. You can demand clarity. You can say: "Show me the real numbers. Not the marketing version."

That’s how you take back control.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is the actual chance of something happening to you - like a 2% chance of a heart attack. Relative risk compares your chance with the drug to your chance without it - like saying the drug cuts your risk by 50%. The same change can sound very different depending on which number you use.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Because relative risk makes small benefits look bigger. A 50% reduction sounds impressive, even if it only means going from 2% to 1%. Absolute risk shows the real impact - and it’s often much smaller. Ads use relative risk to make drugs seem more effective than they really are.

How do I know if a drug’s side effects are serious?

Look at the absolute risk. If 1 in 100 people get a side effect, that’s 1%. That’s common. If 1 in 10,000 get it, that’s 0.01% - rare. A relative risk of 3 might sound scary, but if the original risk was 0.1%, the new risk is just 0.3%. That’s still very low. Always ask: "How many people out of 100 will actually have this?"

What is the Number Needed to Treat (NNT)?

NNT tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit. If the absolute risk reduction is 10% (0.10), then NNT is 10. That means 10 people must take the drug for one person to avoid the bad outcome. A low NNT (like 5) means the drug helps many people. A high NNT (like 100) means it helps very few.

Can I trust my doctor’s explanation of drug risks?

Many doctors aren’t trained to explain risk clearly. A 2019 study found 60% couldn’t convert relative risk to absolute terms. Don’t be afraid to ask for numbers, written materials, or visual aids. If they can’t give you clear answers, ask for a pharmacist or a second opinion. Your health is worth the extra questions.

10 Comments