When a hospital decides which generic drugs to stock, it’s not just about price. It’s about clinical safety, supply reliability, and how well a drug works in real-world hospital settings - not just in a lab. Every year, hospitals spend billions on medications, and generics make up nearly 90% of all drug volumes. But that doesn’t mean they’re all treated the same. The decision-making process behind which generics make it onto a hospital’s formulary is complex, tightly controlled, and driven by data - not just cost-cutting. A hospital formulary isn’t just a list. It’s a living system managed by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee, made up of pharmacists, physicians, and sometimes nurses. This group meets monthly or quarterly to review new drugs, evaluate existing ones, and decide what stays and what gets pulled. Their goal? To balance patient outcomes with institutional budgets. And when it comes to generics, they’re under more pressure than ever. In 2022, the U.S. hospital generic drug market hit $42.7 billion. That’s huge. But here’s the twist: while generics account for 89% of all hospital drug purchases by volume, they only make up 28% of total drug spending. Why? Because the most expensive drugs - often specialty biologics or complex injectables - still dominate the cost side. Generics are the workhorses. But not all generics are created equal.

How P&T Committees Evaluate Generics

The FDA approves a generic drug when it proves bioequivalence to the brand-name version. That means it delivers the same active ingredient at the same rate and amount. But for a hospital P&T committee, that’s just the starting line. They ask harder questions:- Does the generic work the same in critically ill patients with organ failure?

- Is the excipient (inactive ingredient) safe for patients with allergies or kidney disease?

- Can nurses reliably administer it through IV lines without clogging or precipitation?

- Does the packaging make sense in a fast-paced ICU?

The Tiered Formulary System

Most hospitals use a tiered formulary system, usually with three to five levels:- Tier 1: Preferred generics - lowest cost, no prior authorization needed. These are the go-to choices.

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics or preferred brands. May require a prior authorization or step therapy.

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brands. Higher cost, often used only if generics fail.

- Tiers 4-5: Specialty drugs - often biologics or complex injectables. High cost-sharing, strict restrictions.

Hospital vs. Retail: Why the Rules Are Different

Retail pharmacies and Medicare Part D plans operate under completely different rules. Retail formularies focus on outpatient convenience - how easy it is for patients to pick up pills, whether they can store them at home, if the pill size is manageable for seniors. Hospitals don’t care about any of that. They care about:- How quickly a drug works in an emergency

- Whether it can be given through an IV in a trauma bay

- If it interacts with other drugs a patient is already on

- Whether the pharmacy can reliably supply it 24/7

The Hidden Cost of Rebates

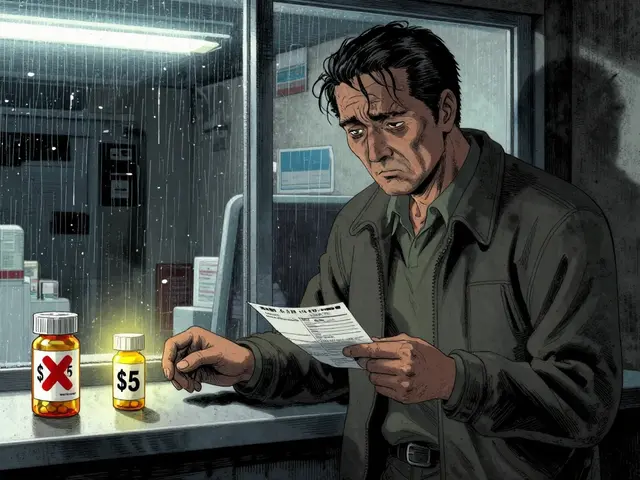

Here’s where it gets messy. Many people assume the lowest list price wins. But in hospitals, rebates and service agreements can flip the script. A generic drug might have a $10 list price. But if the manufacturer offers a 40% rebate, a $6 net cost, and agrees to provide free inventory management software - it becomes the top pick. Meanwhile, a $7 generic with no rebate gets rejected. Dr. Emily Chen, Director of Pharmacy at Massachusetts General Hospital, put it bluntly in a 2023 interview: “The lowest list price doesn’t always mean the lowest net cost.” The problem? These rebate deals aren’t transparent. A 2021 ASHP white paper warned that “rebate-driven formulary decisions” can push hospitals toward drugs that aren’t clinically optimal - especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or phenytoin, where tiny differences in blood levels can mean seizures or strokes.Supply Chain Chaos

In November 2023, the FDA recorded 298 active generic drug shortages - the highest number since tracking began in 2011. Why? Manufacturing issues. Raw material shortages. Single-source production. Regulatory delays. When a key generic vanishes, hospitals scramble. They might have to switch to a more expensive brand, or use a less-studied alternative. A 2023 case study from Mayo Clinic showed that after implementing a well-managed generic substitution program for cardiovascular drugs, they saved $1.2 million annually. But that program only worked because they had backup suppliers, real-time inventory tracking, and pharmacists monitoring for adverse events. Most hospitals aren’t that prepared.

What Makes a Successful Generic Program?

The best-run hospitals don’t just swap brand drugs for generics. They build systems.- Therapeutic interchange committees: Small teams that develop protocols for switching patients from brand to generic, with monitoring steps built in.

- Formulary decision support in EHRs: Only 37% of hospitals have automated alerts that pop up when a prescriber tries to order a non-formulary drug. The rest rely on manual checks - leading to 15-20% non-adherence.

- AMCP dossiers: Since 2020, 92% of academic medical centers require manufacturers to submit detailed dossiers - clinical data, pharmacology, economic analysis - before a generic is even considered.

- Pharmacogenomics: 28% of academic hospitals now factor in genetic testing data when evaluating generics for drugs like clopidogrel or warfarin, where patient genetics affect response.

12 Comments

Man, this post really nailed it. I’ve been on a P&T committee for five years now, and yep - it’s never just about price. I remember when we tried switching to this cheap generic vancomycin because the list price was half. Turned out the excipient reacted with hispidine in the IV bags and caused microclots. Nurses started reporting clogged lines every shift. We had to pull it after two weeks. Cost us more in overtime than we saved. The FDA says ‘bioequivalent’ - hospitals say ‘does it work in real life?’

OMG I LOVE THIS POST SO MUCH LIKE I’M CRYING RN 😭 like in India we have this thing where hospitals buy generics from like 5 different manufacturers and then the nurses just grab whatever’s in the cart and give it to patients and like half the time the tablets are cracked or the capsules are leaking and we don’t even know what’s inside but hey at least it’s cheap right?? like my cousin was in ICU and they gave her this generic metformin and she had a seizure because the filler was toxic and no one even tested it?? like why do we even have standards if we don’t enforce them?? i mean i get it budget budget budget but like if your patient dies because you saved 3 cents per pill is that a win?? 🤯

So let me get this straight - hospitals are using rebates as a secret backdoor to push drugs that aren’t clinically better, and we’re surprised when patients have strokes? Wow. Groundbreaking. Next you’ll tell me water is wet.

Therapeutic interchange protocols are the unsung heroes here. We implemented one at our hospital last year - pharmacists flag potential switches in the EHR, then do a quick chart review with the MD before dispensing. Adverse events dropped 40%. The key? Not cost. Consistency. Documentation. And yeah, having a pharmacist who actually talks to the nurse before the med goes in.

You people are so naive. This whole system is a scam. The manufacturers bribe the P&T committees with ‘free software’ and ‘educational grants’ - it’s all just pharma grease money in a lab coat. And don’t even get me started on the fact that 70% of these generics are made in one factory in Gujarat with no OSHA oversight. We’re not saving lives - we’re gambling with people’s kidneys. This isn’t healthcare. It’s Russian roulette with IV bags.

As someone who grew up in a rural town where the nearest hospital was 90 miles away, I just want to say - this matters. I’ve seen people skip meds because they couldn’t afford the brand, then end up back in ER. Generics saved my dad’s life. But I also saw a guy get a bad batch of generic levothyroxine and go into atrial fibrillation. It’s not black and white. We need better testing. More transparency. Not just cheaper.

Just saw this on my feed and had to chime in - we rolled out a new generic substitution protocol at our hospital last quarter. We didn’t just go by price. We looked at supplier reliability, batch failure rates, and even nurse feedback on how easy it was to draw up. We switched from a $2.50 generic to a $3.10 one because the packaging had child-safe caps and the vials didn’t leak. Guess what? Adverse events dropped 30%. Sometimes the ‘expensive’ option is the real bargain.

Oh sweet merciful Jesus on a pogo stick - you mean to tell me that hospitals are actually thinking about *clinical outcomes* and not just the bottom line? 🤯 I thought we were all just chasing rebate percentages like a bunch of Wall Street raccoons. This is the most human thing I’ve read all year. Also - GDUFA III? That’s the FDA’s ‘let’s stop making inhalers impossible to copy’ program? FINALLY. Took them long enough. 62% first-pass approval? That’s criminal. We need more labs. More inspectors. More funding. Not more PowerPoint slides.

Big picture: This is why we need national drug safety standards for generics. Not state-by-state. Not hospital-by-hospital. The FDA approves - but hospitals are the ones who actually use it. We need mandatory real-world outcome tracking for every generic. Like, mandatory post-market surveillance. If a drug causes 3+ adverse events in 30 days, it gets pulled. Simple. No rebates. No lobbying. Just data. And yeah - I know it’ll be a nightmare to implement. But we’ve got the tech. We’ve got the data. We just need the guts.

so like... if a generic is cheaper but makes people sick... is it really a savings? 🤔

My hospital just switched to a new generic for amiodarone last month. We had a 200% spike in QT prolongation cases. We pulled it. The manufacturer said it was ‘bioequivalent’. We said ‘prove it in real patients’. They didn’t. We went back to the brand. Cost us $180K extra this quarter. But we didn’t have a single cardiac arrest. Sometimes the ‘expensive’ choice is the only ethical one. Also - can we please stop pretending that ‘formulary’ is just a fancy word for ‘budget cut’? It’s a clinical decision-making framework. Not a spreadsheet.

so like... i work in a hospital and we just got this new generic for insulin and it's like... the label says '100 units/mL' but the vial has 98.5? like... who even checks this?? 😭