It’s not unusual to walk out of the pharmacy with a prescription in hand and feel completely unsure how to take your medicine. Is it before or after food? Once a day or twice? At the same time every day or whenever you feel like it? You’re not alone. A medication instruction that seems simple can hide dangerous ambiguity - and the consequences aren’t just inconvenient, they can be life-threatening.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices reports that unclear directions contribute to over 1.5 million medication-related injuries in the U.S. every year. That’s not a small number. It’s not a rare glitch. It’s a systemic problem that happens because prescriptions are often written with shorthand, outdated abbreviations, or conflicting details between different brands of the same drug. You’re expected to understand it all - but no one ever taught you how to ask the right questions.

Why Medication Instructions Get So Confusing

Prescriptions aren’t written for patients - they’re written for healthcare professionals. That means they often use shortcuts that make sense in a hospital or clinic but leave patients lost. For example:

- “q.d.” instead of “daily” - this can be mistaken for “q.i.d.” (four times a day)

- “IN” for intranasal - looks like “IV” (intravenous) or “IM” (intramuscular)

- “d” in “mg/kg/d” - does that mean day or dose? Both are used in medical writing

- “take as needed” - needed for what? Pain? Anxiety? How many times is too many?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started requiring Medication Guides in 1998 for high-risk drugs like opioids, isotretinoin, and birth control pills. These are printed handouts you’re supposed to get when you pick up the medicine. But here’s the catch: they’re only required for about 200 drugs out of thousands. Most of your prescriptions? No guide. No safety net.

Even worse, different manufacturers of the same generic drug can have different instructions. One brand says to take it with food. Another says to take it on an empty stomach. One says twice daily at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Another says “every 12 hours.” Which one do you follow? Your doctor may not even know the difference.

What You Should Do When Instructions Don’t Make Sense

Don’t guess. Don’t assume. Don’t just take it and hope for the best. Here’s exactly what to do:

- Read the label again - slowly. Look for the “Sig” section - that’s the directions written by the prescriber. If it says “one tab po q am,” that means “one tablet by mouth every morning.” But if you’re not sure, don’t pretend you know.

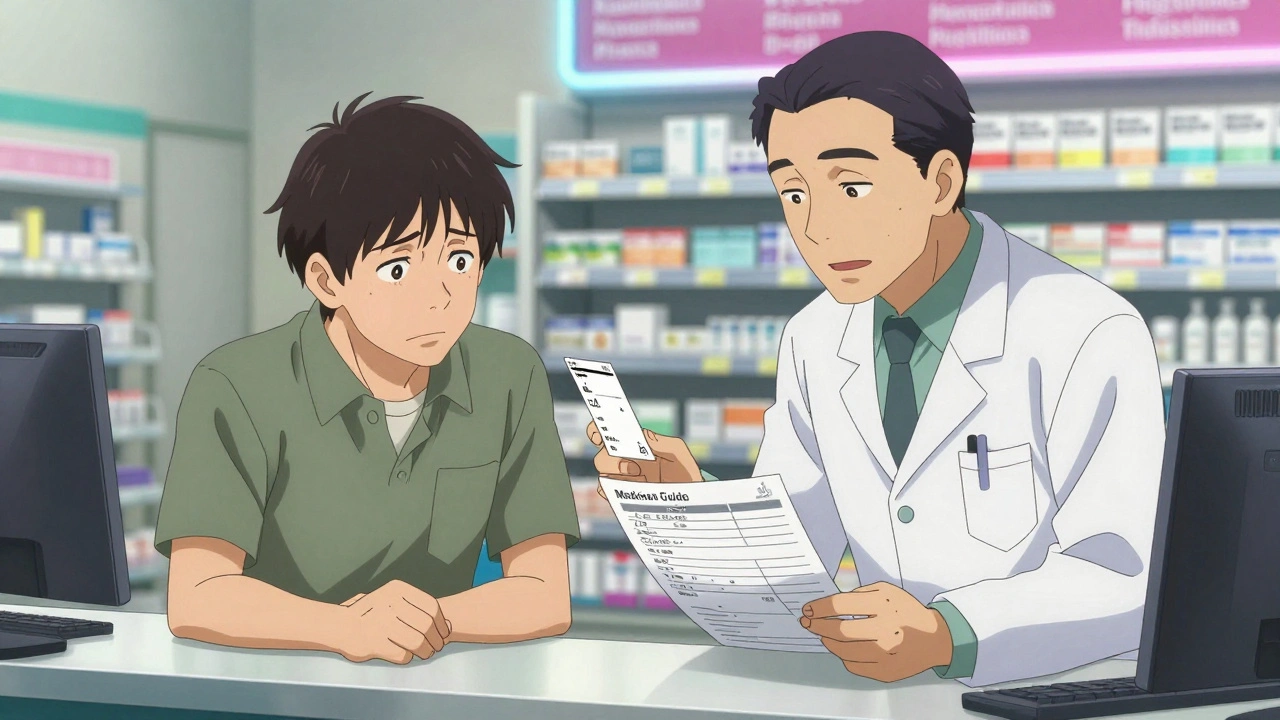

- Ask the pharmacist - specifically. Don’t just say, “Is this right?” Ask: “Can you explain how I’m supposed to take this? What time of day? With or without food? What happens if I miss a dose?” Pharmacists are trained to spot dangerous wording and can clarify what the doctor meant.

- Check for a Medication Guide. If it’s one of the 200+ FDA-mandated drugs, you should get a printed guide. If you didn’t get one, ask for it. You’re legally entitled to it. You can also request an electronic copy if you prefer.

- Compare manufacturer instructions. If you’ve taken this drug before from a different pharmacy, and the directions changed, bring both bottles in. Ask: “Why are these different? Which one should I follow?”

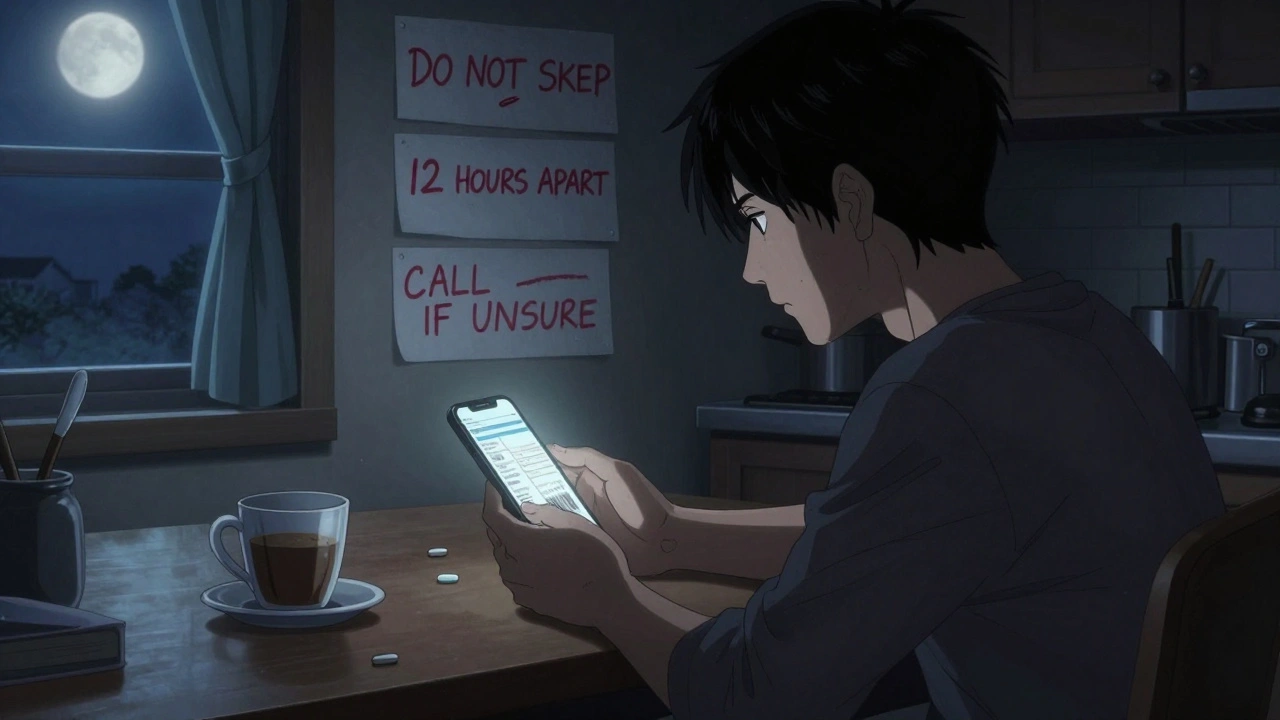

- Write it down. Don’t rely on memory. Write the instructions in plain language: “Take one 500 mg tablet every morning with breakfast. Do not take more than one tablet in 24 hours.” Keep it on your fridge or phone.

Harvard Health says if you’re unsure - even if it was explained to you before - ask again. There’s no shame in it. In fact, the most dangerous patients are the ones who pretend they understand.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

It’s not just about how much you take - it’s when you take it. Timing affects how well the drug works - and whether it causes side effects.

Cholesterol-lowering statins, for example, are usually taken at bedtime because your liver makes most of your cholesterol overnight. Taking them in the morning cuts their effectiveness. Blood pressure meds? Often taken in the morning to control spikes during the day. But some newer ones are designed for evening use to prevent early-morning heart risks.

“Twice daily” doesn’t mean “when I remember.” It means as close to 12 hours apart as possible - like 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Taking it at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. might seem fine, but that’s only 10 hours. That small difference can let your condition flare up.

“Take as needed” is one of the most dangerous phrases. It doesn’t mean “whenever you feel like it.” It means “only when you have a specific symptom, and only up to a certain number of times per day.” For example, a painkiller labeled “take as needed” might have a maximum of four doses in 24 hours, with at least six hours between doses. If you don’t know that limit, you could overdose.

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

Medication errors aren’t just about taking too much. Sometimes it’s taking too little. Or taking it at the wrong time. Or mixing it with something you shouldn’t.

Take warfarin, a blood thinner. If you’re told to take it daily but you skip a day, your blood can clot. If you take two by accident, you could bleed internally. Neither outcome is rare.

Or consider insulin. If you’re told to take it before meals but you don’t know how much to eat, you could crash your blood sugar. Or if you’re told to take it after meals and you take it before, you could end up in the hospital.

The CDC says 4 out of 5 American adults take at least one medication. One in four take three or more. The more you take, the higher the chance of a dangerous mix-up. That’s why clarity isn’t optional - it’s a survival skill.

How to Talk to Your Doctor Without Feeling Awkward

You don’t need to be an expert to ask for help. Here’s how to say it without sounding like you’re accusing your doctor:

- “I want to make sure I’m taking this right. Can you walk me through it one more time?”

- “I’ve taken this before, but the instructions changed. Can you help me understand why?”

- “I’m worried I might be taking it wrong. What’s the worst that could happen if I get it wrong?”

- “Can you write the instructions in plain English? Not medical shorthand.”

Doctors appreciate patients who ask. It means you’re engaged. It reduces their risk of liability. And it saves lives.

Tools That Can Help

You don’t have to rely on memory or paper notes. Use these free tools:

- Medication reminder apps like MyTherapy or Medisafe - they send alerts, track doses, and let you share logs with family or doctors.

- Pharmacy apps - most big chains let you view your prescriptions, see instructions, and message your pharmacist directly.

- Barcode scanning - some apps let you scan the pill bottle to get detailed info, including side effects and interactions.

The CDC recommends setting alarms for medications that need to be taken at specific times. If you’re on a complex schedule - say, five pills at different times - a simple phone alarm labeled “AM: Blood pressure + Thyroid” can prevent a mistake.

What to Do If You Already Made a Mistake

If you took a pill at the wrong time, doubled a dose, or skipped a few days - don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either.

Call your pharmacist or doctor and say: “I think I took my medication wrong. Here’s what happened…” Be specific. They’ve heard it all before. They won’t judge. They’ll tell you what to do next.

For high-risk drugs like blood thinners, insulin, or seizure meds, never wait. Call immediately. For others, wait until the next business day - but don’t wait longer.

And next time, write it down. Set the alarm. Ask the question.

12 Comments

This system is a goddamn joke. I’ve had prescriptions where the pharmacist couldn’t even read the scribble, and the doctor didn’t care. I once took a pill labeled ‘q.d.’ and ended up in the ER because I thought it meant ‘quarter dose.’ Turns out it was ‘daily.’ And yeah, I’m still pissed.

They don’t write for patients because patients aren’t worth the effort. We’re just meat sacks with insurance numbers. If you don’t figure it out, you die. That’s the unspoken rule.

And don’t get me started on generic brands. I got the same drug from two different pharmacies - one said take with food, the other said empty stomach. Both were ‘generic lisinopril.’ Guess what? My blood pressure went nuts. No one apologized. No one even blinked.

They’re not trying to kill us. They’re just too lazy to care. And we’re too scared to ask because we think we’ll sound stupid. Newsflash: you’re not stupid. The system is broken.

I’ve started printing out the FDA Medication Guides and taping them to my fridge. If I have to be a detective just to not overdose, then I’m doing it right. Screw ‘trust your doctor.’ Trust your damn notes.

And if you’re still taking ‘as needed’ without a written limit? You’re playing Russian roulette with your liver. Stop it.

The real tragedy isn’t the ambiguity in prescriptions - it’s the normalization of it. We’ve been conditioned to accept medical obfuscation as inevitable, like bad Wi-Fi or delayed flights. But this isn’t a glitch. It’s a feature of a profit-driven system that treats patient comprehension as an afterthought.

Pharmacists are the last line of defense, yet they’re overworked, underpaid, and often legally restricted from correcting prescribing errors. The burden of clarity is placed on the patient, who has zero training in pharmacology, while the professionals who wrote the script walk away unscathed.

Medication Guides exist for 200 drugs out of thousands. That’s not a safety net. That’s a lottery ticket. And if you’re on five medications? You’re playing the odds every single day.

Writing instructions down helps, yes. But it doesn’t fix the root problem: medicine was never designed for laypeople. It was designed for efficiency. And efficiency, in this context, means silence from the patient and liability avoidance from the provider.

We need mandatory plain-language labeling. Not suggestions. Not guidelines. Law. And we need audits. If a prescription uses ‘q.d.’ or ‘d’ without context, it should be rejected. Period.

Consider the epistemological framework of pharmaceutical authority. The physician, as a gatekeeper of symbolic capital, transmits encoded directives through a semiotic system alien to the lay subject. The patient, rendered epistemologically inferior, is compelled to perform compliance without epistemic access to the code.

Thus, the ‘Sig’ section is not merely a set of instructions - it is a ritual of subordination. The Medication Guide, when provided, is a performative gesture of institutional benevolence, not a right. The FDA’s 200-drug mandate reveals a hierarchy of risk: some lives are deemed worthy of clarity; others, disposable.

When you ‘ask again,’ as Harvard suggests, you are not seeking clarification - you are challenging the ontological privilege of the medical class. And they hate that.

So we turn to apps. We scan barcodes. We set alarms. We become our own pharmacists. Because the system will never change. It was never meant to.

And yet - the very act of documenting, of questioning, of writing in plain English - is a quiet act of rebellion. A reclamation of the body from the algorithm of negligence.

Just wanted to say this post saved my mom’s life. She’s on six meds, and she used to just guess. One time she took her blood thinner at night instead of morning - turned out it was causing internal bleeding. We didn’t know until she passed out.

After that, we started using Medisafe. Now she gets alerts, I get copies, and we print out the instructions for each pill. We even took both bottles to the pharmacy when the generic changed.

It’s not hard. It just takes a little effort. And yeah, it’s frustrating that we have to do this at all. But if it keeps someone alive? Worth it.

Also, I always ask the pharmacist: ‘Is this the same as last time?’ They’re usually happy to help. Most of them are amazing.

Thanks for writing this. Needed to hear it.

The root issue lies in the misalignment between pharmacokinetic protocols and patient-centered communication paradigms. The prescriptive lexicon remains entrenched in Latin-derived abbreviations and clinician-centric syntax, which are antithetical to cognitive load theory in lay populations.

Moreover, the absence of standardized pharmacogenomic labeling across generic manufacturers introduces therapeutic equivalence ambiguity - a phenomenon empirically documented in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 2021.

While behavioral interventions such as written documentation and app-based reminders are mitigative, they do not resolve the structural deficit: the commodification of pharmaceutical literacy. The burden of comprehension is externalized to the patient, who lacks the requisite metadata to decode the prescriptive signal.

Until regulatory bodies mandate plain-language labeling with ISO 15285 compliance, we are merely applying bandages to a hemorrhage.

I’m a nurse, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen patients scared to ask because they think they’ll be judged. They’re not. We’ve all been there.

I always tell my patients: ‘If you’re unsure, write it down. Say it out loud. Record it on your phone. Even if you’ve taken it before - things change. Always check.’

And if you’re on more than three meds? Get a pill organizer. Use the pharmacy app. Don’t rely on memory. I’ve seen people take the wrong pill because they looked similar. It’s terrifying.

You’re not being difficult. You’re being smart. And if your pharmacist doesn’t have time to explain? Go to another one. There are good ones out there. You deserve clarity.

And if you’re reading this and thinking ‘I don’t have time’ - I get it. But your life is worth the 3 minutes it takes to ask.

This is the kind of post I wish I’d read five years ago. I used to take my thyroid med with coffee because I thought it didn’t matter. Turns out caffeine blocks absorption. My TSH levels were all over the place for months. No one told me.

Now I take it first thing in the morning, wait an hour, then drink coffee. Simple. But I only learned it because I asked. And I asked again. And again.

Don’t be shy. Don’t feel dumb. You’re not the problem. The system is. And you’re doing the right thing by caring enough to ask.

Also - yes, write it down. I keep mine in my phone notes under ‘My Meds.’ I even added why each one matters: ‘This one keeps my heart from racing. This one stops my hands from shaking.’ It helps me remember why I’m doing this.

You’ve got this. And you’re not alone.

Is clarity even possible in a system where knowledge is power and power is profit? The prescription is not a document - it is a transaction. The patient’s understanding is irrelevant if compliance is enforced through fear of consequence rather than through shared meaning.

When we ‘ask again,’ are we seeking truth - or merely permission to survive?

The Medication Guide is a performative artifact. A token. A legal shield for the manufacturer. It does not grant understanding. It grants liability coverage.

And yet - we persist. We write. We scan. We set alarms. We become archivists of our own survival. Not because we are empowered - but because we have no other choice.

Is this medicine? Or is this survival theater?