Peptic ulcer disease isn’t just a bad stomach ache. It’s a real break in the lining of your stomach or upper intestine - a wound that doesn’t heal on its own. Around 8 million people worldwide live with it right now, and for most, it’s not because they ate too much spicy food. The real culprits are far more specific: a stubborn bacteria called H. pylori and common painkillers like ibuprofen or aspirin. The good news? It’s one of the most treatable conditions in gastroenterology - if you know what you’re up against.

What’s Really Causing Your Ulcer?

For decades, doctors thought stress and diet caused peptic ulcers. That myth stuck around long after science proved it wrong. Today, we know two main triggers make up over 90% of cases.Helicobacter pylori is the biggest offender. This spiral-shaped bacteria lives in the stomach lining, where it survives the acid by burrowing into the mucus layer. Once there, it triggers inflammation, weakens the protective barrier, and lets stomach acid burn through the tissue underneath. It’s present in more than half of all duodenal ulcers and in 30 to 50% of gastric ulcers.

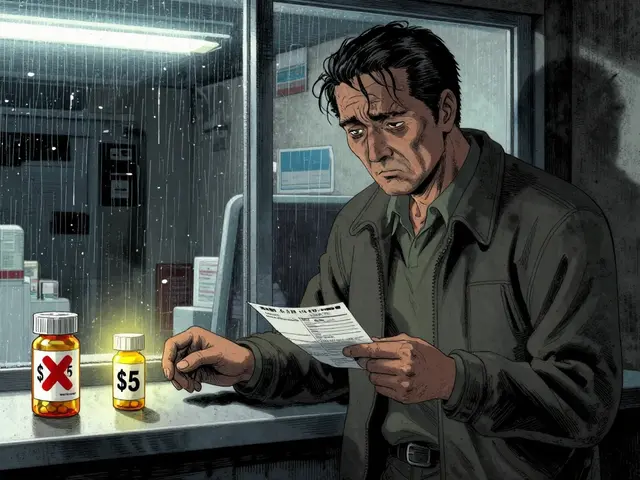

The second major cause? Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - or NSAIDs. That’s everything from Advil and Aleve to low-dose aspirin taken for heart health. These drugs block enzymes that help protect the stomach lining. Without that protection, acid eats away at the tissue. NSAIDs now cause more ulcers than H. pylori in many places, especially among older adults who take them daily for arthritis or chronic pain.

Other factors like smoking and heavy alcohol use don’t cause ulcers directly, but they make them worse. Smoking doubles or triples your risk of developing one. Drinking more than three alcoholic drinks a day bumps up your risk by 300%. Even if you’re not taking NSAIDs or infected with H. pylori, these habits can keep an ulcer from healing.

How Do You Know You Have One?

Symptoms can be subtle or severe. The classic sign is a burning or gnawing pain in the upper belly - right below the breastbone. For many, the pain comes and goes. It often feels better after eating or taking an antacid, then returns a couple of hours later. That’s because food temporarily neutralizes acid, giving the ulcer a short break.Other common signs include:

- Feeling full quickly during meals

- Nausea or vomiting

- Bloating or burping

- Intolerance to fatty or greasy foods

- Loss of appetite and unintended weight loss

Red flags? Don’t ignore them. Vomiting blood (which might look like coffee grounds), black or tarry stools, or sudden, sharp abdominal pain could mean the ulcer has bled or perforated. These are emergencies. If you’re over 50 and suddenly develop new stomach pain, your doctor will likely want to rule out cancer - ulcers can sometimes mask it.

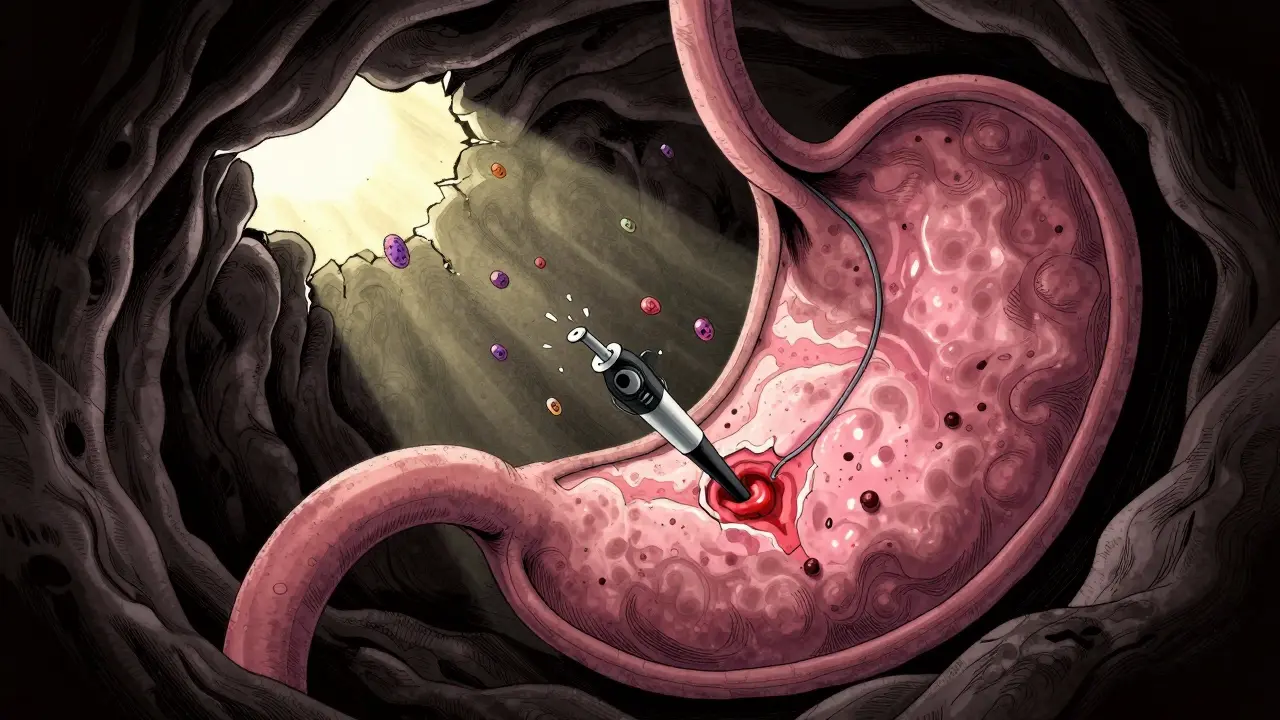

Diagnosis isn’t guesswork. You need a test. Endoscopy - where a thin camera is passed down your throat - is the gold standard. It lets the doctor see the ulcer directly and take a biopsy. But you’ll also get tested for H. pylori. That’s usually done with a breath test, stool test, or blood test. If you’re on PPIs or antibiotics, those can mess with the results, so your doctor might ask you to stop them first.

Antibiotics: The Real Cure for H. pylori

If H. pylori is the cause, antibiotics are the only way to get rid of it for good. And here’s the key: you don’t take just one. You take two at the same time - along with a strong acid-reducing drug. This combo is called triple therapy.Typical regimens include:

- Pantoprazole (a PPI) + clarithromycin + amoxicillin

- Pantoprazole + clarithromycin + metronidazole

You take these for 7 to 14 days. The antibiotics kill the bacteria. The PPI shuts down acid so the stomach lining can heal. Missing even one dose can let the bacteria survive - and become resistant. That’s why adherence is critical. One study showed that over half of treatment failures were due to patients stopping early because they felt better.

Side effects are common. Metallic taste (especially with metronidazole), nausea, diarrhea, and a bitter mouth feel are typical. Some people describe it as feeling like they’re chewing on a battery. But these symptoms usually fade after treatment ends. If they’re unbearable, talk to your doctor - there are alternative combinations.

In areas where clarithromycin resistance is high - now over 35% in the U.S. - doctors are switching to quadruple therapy. That adds bismuth (like Pepto-Bismol) to the mix. It’s more pills, more side effects, but it works better where resistance is common. New guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology now recommend this as first-line in many regions.

Acid-Reducing Medications: Healing the Damage

Even if you don’t have H. pylori, you still need to calm the acid. That’s where acid-reducing meds come in. There are two types: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers.PPIs are the first choice. They work by shutting down the acid pumps in your stomach cells. That’s powerful. One dose lasts 24 to 72 hours. Common ones include:

- Omeprazole (Prilosec)

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- Pantoprazole (Protonix)

- Rabeprazole (AcipHex)

They’re taken 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast (and sometimes dinner) for maximum effect. Taking them after a meal? That cuts their power in half.

H2 blockers like famotidine (Pepcid) or ranitidine (Zantac - now pulled from most markets) work differently. They block histamine, which signals acid production. They’re weaker than PPIs and last only 10 to 12 hours. They’re still useful for nighttime symptoms, but PPIs heal ulcers faster and more completely.

For NSAID-induced ulcers, stopping the drug is ideal. But if you can’t - maybe you’re on daily aspirin for your heart - your doctor might put you on a long-term PPI. Some even add misoprostol, a drug that replaces protective mucus your body stops making when you take NSAIDs.

What About Long-Term Use of PPIs?

PPIs are safe for most people in the short term. But if you’re on them for months or years - especially at high doses - there are risks. The FDA has issued warnings about:- Increased risk of bone fractures (especially in older adults)

- Low vitamin B12 levels (because acid is needed to absorb it)

- Higher chance of C. diff infection (a serious gut infection)

- Acute interstitial nephritis (a rare kidney problem)

Most of these risks are tied to high-dose, long-term use - not the 4 to 8 weeks you’d take after an ulcer heals. Still, if you’ve been on a PPI for over a year, talk to your doctor about whether you still need it. Some people develop rebound acid reflux after stopping, which feels like the ulcer is back. That’s not a relapse - it’s your stomach overproducing acid temporarily. It fades in a few weeks.

Don’t quit cold turkey. Work with your doctor to taper off slowly, maybe switch to an H2 blocker first, or use lifestyle changes like eating smaller meals and avoiding late-night snacks.

What’s New in Ulcer Treatment?

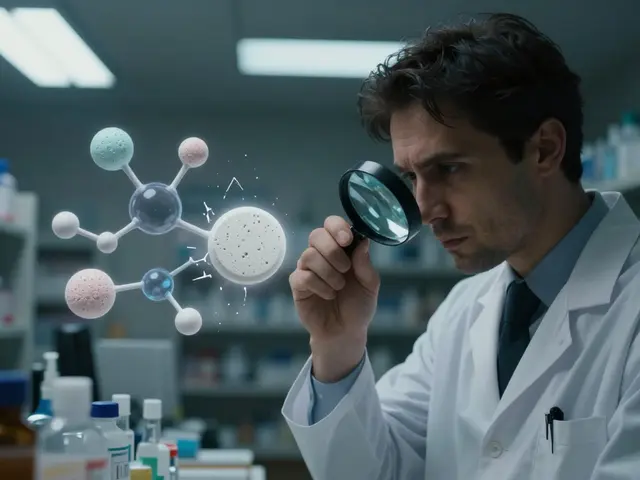

The field is changing fast. In January 2023, the FDA approved a new drug called vonoprazan. It’s not a PPI - it’s a potassium-competitive acid blocker. It works faster, lasts longer, and suppresses acid more completely. In trials, it achieved 90% H. pylori eradication rates - better than the 75-85% you get with standard PPIs.Another big shift? Testing for antibiotic resistance before treatment. In 2022, only 15% of U.S. doctors did this. By 2025, the American Gastroenterological Association expects that number to hit 60%. That means your doctor might test your H. pylori strain to see which antibiotics will actually work - no more guessing.

As the population ages and more people rely on NSAIDs for chronic pain, ulcers from painkillers won’t go away. But with smarter testing, better drugs, and clearer guidelines, we’re getting better at stopping them before they start.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you think you have an ulcer, don’t wait. See a doctor. Don’t self-treat with antacids or OTC PPIs for more than two weeks. That can hide a bigger problem.If you’re diagnosed:

- Take every pill, exactly as prescribed - even if you feel better.

- Stop NSAIDs unless your doctor says otherwise. Use acetaminophen (Tylenol) instead for pain.

- Quit smoking. It’s one of the biggest barriers to healing.

- Limit alcohol. More than three drinks a day makes ulcers worse.

- Don’t stress about spicy food - it doesn’t cause ulcers, but if it bothers you, skip it.

Healing takes time. Most ulcers start to improve in days, but full healing takes 4 to 8 weeks. Stay on your meds. Follow up. Get retested for H. pylori after treatment - usually 4 weeks after finishing antibiotics - to make sure it’s gone.

Peptic ulcer disease isn’t a life sentence. It’s a fixable problem. With the right diagnosis, the right meds, and the right habits, you can be symptom-free and ulcer-free - for good.

12 Comments

Bro, I swear the FDA is just in bed with Big Pharma. They want you on PPIs forever so you keep buying them. H. pylori? Nah, it’s the glyphosate in your food. I read a guy on Telegram who cured his ulcer with turmeric and moonwater. No pills. Just vibes. 🌙

OMG YES this is so important!! 🙌 I had an ulcer last year and thought it was just ‘stress’ - turns out I was on ibuprofen for months for my migraines 😅 So glad I found this. Your post saved me from years of suffering. Thank you!! 💖

Let me just say this with absolute clarity: if you’re still treating ulcers with antacids or ‘diet changes,’ you’re doing it wrong. The science is settled - H. pylori and NSAIDs are the root causes, period. And if your doctor isn’t testing for resistance before prescribing antibiotics, find a new one. Triple therapy is outdated in 2024. Quadruple with bismuth is the new standard, and anyone who tells you otherwise hasn’t read the ACG guidelines since 2022. Also, yes, PPIs have risks - but those risks are astronomically lower than the risk of a perforated ulcer. Don’t let fear of side effects make you skip the treatment that saves your life.

Just wanted to say - this is the kind of post that makes Reddit worth it. No fluff, no hype, just straight facts with real clinical weight. I’m a med student and I wish more docs wrote like this. Also, side note: the ‘chewing on a battery’ description? 10/10. That’s exactly how metronidazole tastes. I still gag thinking about it.

I think what’s beautiful here is how this post bridges science and lived experience. It’s not just ‘take these pills’ - it’s ‘here’s why, here’s how, and here’s what to watch for.’ I’ve seen too many people get dismissed with ‘it’s just acid’ when it’s something much deeper. Thank you for honoring the complexity.

The epistemological shift in gastroenterology regarding peptic ulcer disease represents a paradigmatic triumph of empirical inquiry over anecdotal dogma. The once-ubiquitous attribution to psychological stress, while culturally resonant, was ultimately a misattribution born of epistemic limitation. The discovery of Helicobacter pylori as a primary etiological agent, validated through Koch’s postulates and corroborated by molecular diagnostics, exemplifies the self-correcting nature of scientific medicine. One cannot help but reflect on the sociological inertia that prolonged the myth - a testament to the power of narrative over data in public consciousness.

So you’re telling me the entire medical establishment got it wrong for 50 years… and now they’re just gonna fix it with more pills? Sounds like a profit-driven reset to me. What about the real cause? EMF radiation from phones. I’ve seen 3 people cure their ulcers by sleeping with their phones in the fridge. Just saying.

Wow. So now we’re supposed to believe antibiotics are the answer? But what about the gut microbiome? You’re just going to wipe it all out and call it a day? And PPIs? You know they cause dementia, right? I read it on a blog written by a guy who used to be a pharmacist. He’s now a ‘wellness coach.’

In Japan, we treat ulcers with a lot of fermented foods and mindfulness. It’s not just about killing bacteria - it’s about restoring balance. I’ve seen patients heal with miso soup, daily breathing exercises, and avoiding cold drinks after meals. Western medicine focuses on eradication, but Eastern tradition focuses on harmony. Both have value.

MY UNCLE DIED FROM THIS. I SAW IT. HE TOOK THE PILLS, FELT BETTER, STOPPED, AND THEN - BANG - he was gone. No warning. Just… gone. They told him it was ‘healed.’ But it wasn’t. I swear to God, the system is lying to us. I don’t trust doctors anymore. I don’t trust ANYTHING.

h. pylori is a hoax. its a government bioweapon to sell ppi. i saw a video on yt where a guy in russia used garlic and vodka to kill it. also, the FDA is owned by pfizer. i took 2 tsp of apple cider vinegar every day and my ulcer vanished in 3 days. no science needed.

Wow, so you’re telling me I shouldn’t take ibuprofen for my back pain? But my doctor said it’s fine. And now you want me to switch to Tylenol? That’s the same stuff that killed my cousin’s liver. 😅 Also, I’m not quitting smoking. I’ve been a smoker since 15. My ulcer? It’s just my ‘soul’s way of saying I need a break.’