When a generic drug hits the market, you might wonder: Is it really the same as the brand-name version? The answer isn’t just about ingredients or packaging. It’s about what happens inside your body - how fast the drug gets in, and how much of it stays there. That’s where Cmax and AUC come in. These two numbers aren’t just jargon. They’re the foundation of bioequivalence, the scientific proof that a generic drug works just like the original.

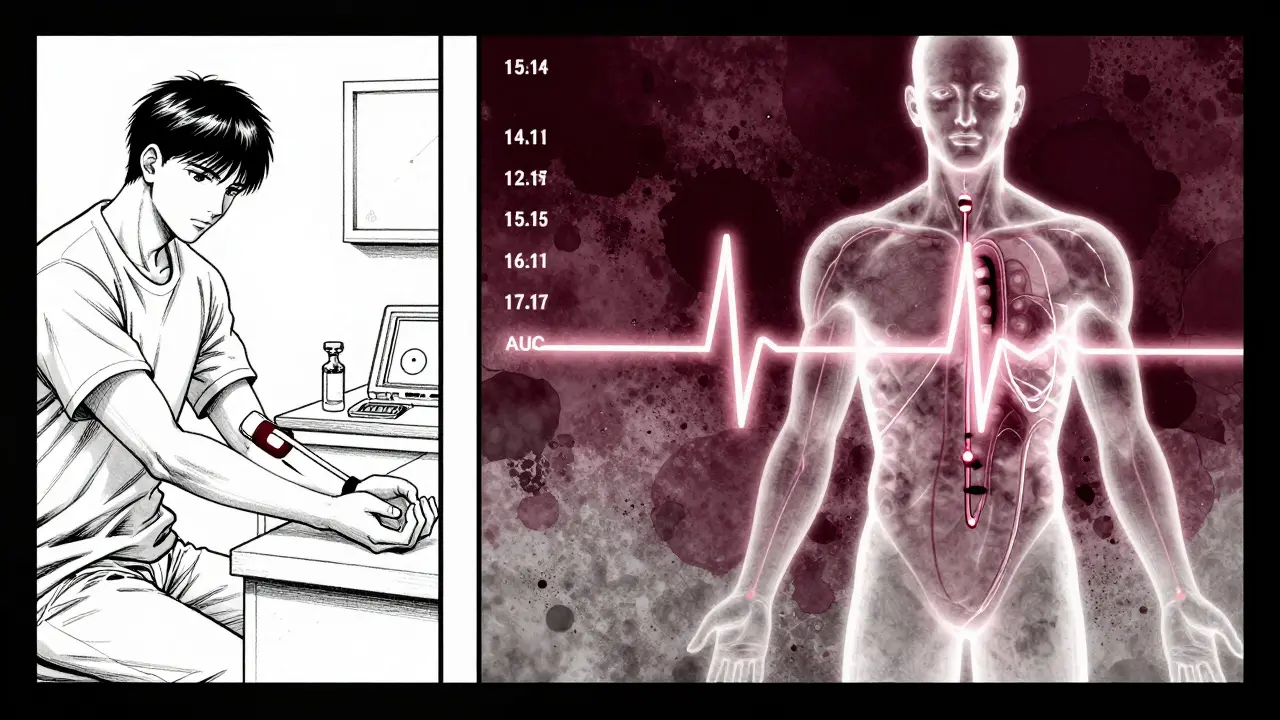

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration. It’s the highest level of the drug in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph - it tells you how strong the drug’s effect might be at its strongest point. If you’re taking a painkiller, a high Cmax means you feel relief faster. But if it’s a drug with a narrow safety window, like warfarin or digoxin, a spike too high could be dangerous.

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total exposure. It’s the entire space under the drug concentration graph from the moment you take it until it’s mostly cleared. This isn’t just about how high the peak is - it’s about how long the drug sticks around. AUC tells you the overall dose your body receives. For antibiotics or antidepressants, where sustained levels matter more than quick bursts, AUC is the key metric.

Both are measured in real units: Cmax in milligrams per liter (mg/L), AUC in milligram-hours per liter (mg·h/L). These aren’t abstract ideas. They’re based on actual blood samples taken from volunteers over hours or days. Modern labs use ultra-sensitive tools like LC-MS/MS to detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter - enough to track even tiny doses accurately.

Why Both Numbers Are Required

You might think: if AUC shows total exposure, why do we even care about Cmax? Because drugs don’t just disappear and reappear - they’re absorbed at different speeds. Two pills can have the same total AUC but very different Cmax values. One might release the drug slowly, giving you a low, steady level. The other might dump it all at once, creating a sharp spike.

That difference matters. For drugs that need to hit a certain threshold quickly - like fast-acting insulin or seizure medications - a low Cmax could mean the drug doesn’t work when you need it most. On the flip side, a too-high Cmax might cause side effects even if the total exposure (AUC) is fine.

Regulators like the FDA and EMA don’t just look at one number. They require both Cmax and AUC to pass. It’s not enough for one to be within range - both have to meet the standard. This dual-check system exists because real-world outcomes depend on both how much drug you get and how fast you get it.

The 80%-125% Rule - Where It Came From

So how do you decide if two drugs are equivalent? The rule is simple: the ratio of the generic’s Cmax and AUC to the brand’s must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand’s average Cmax is 10 mg/L, the generic’s must be between 8 and 12.5 mg/L. Same for AUC.

This range didn’t come out of thin air. It was chosen in the early 1990s based on statistical analysis and decades of clinical data. The 20% difference threshold was determined to be clinically insignificant for most drugs. In other words, if the exposure varies by less than 20%, your body won’t notice a difference in how the drug works or how safe it is.

The math behind it uses logarithms because drug concentrations don’t follow a normal bell curve - they follow a log-normal distribution. That means the difference between 80% and 100% isn’t the same as between 100% and 125% on a linear scale. On a log scale, both are exactly 0.2231 units apart. This symmetry makes the math fair and consistent across all drugs.

But here’s the catch: this rule isn’t universal. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - where small changes can cause big problems - regulators sometimes tighten the range to 90%-111%. That’s the case for levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and warfarin. In these cases, even a 10% drop in exposure could mean your thyroid levels go off track or your blood doesn’t clot properly.

How Bioequivalence Studies Are Done

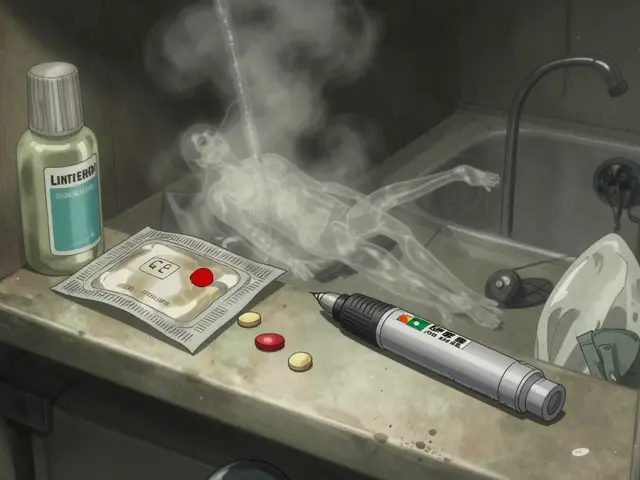

These numbers don’t appear magically. They come from clinical studies - usually in 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Each person takes both the brand and generic versions, in random order, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn every 15 to 60 minutes for up to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life.

The timing of those blood draws is critical. If you miss the first 1-2 hours after dosing, you might completely miss the Cmax peak - especially for fast-absorbing drugs. Studies show that about 15% of bioequivalence trials fail simply because sampling was too sparse during absorption. That’s why guidelines insist on real-time sampling, not just scheduled times.

Once the data is collected, it’s fed into specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin. The values are log-transformed, ratios are calculated, and 90% confidence intervals are built. Only if both intervals fall within 80%-125% does the drug qualify as bioequivalent.

These studies are expensive - often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars - but they’re far cheaper than running large clinical trials to prove the drug works the same. That’s why bioequivalence testing became the backbone of the generic drug industry after the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984. Today, over 1,200 generic approvals in the U.S. alone each year rely on this method.

When the Standard Rule Isn’t Enough

Not all drugs play by the same rules. Some, like those with high variability - where the same person’s response changes dramatically from dose to dose - break the mold. For these, the 80%-125% range can be too strict. A drug might be perfectly safe and effective, but its Cmax or AUC might bounce around due to individual differences in metabolism, food intake, or gut absorption.

The EMA allows a workaround called scaled average bioequivalence for these cases. It lets the acceptable range widen based on how variable the reference drug is. The FDA has similar rules but requires more justification. This is still debated among scientists - some argue it opens the door to weaker generics, while others say it prevents good drugs from being blocked by arbitrary limits.

Another emerging area is complex formulations - like extended-release pills that release drug in two waves. For these, the total AUC might look fine, but if the second peak is too low, the drug might not last long enough. That’s why the FDA is now exploring partial AUC measurements - looking at exposure during specific time windows - to better capture how these drugs behave.

What This Means for You as a Patient

Here’s the bottom line: if a generic drug has passed bioequivalence testing with Cmax and AUC within the approved range, it’s as safe and effective as the brand-name version. A 2019 meta-analysis of 42 studies found no meaningful difference in outcomes between generics and originals when bioequivalence criteria were met.

That doesn’t mean everyone feels the same. Some people report feeling different on a generic - especially if they’ve been on the brand for years. But these differences are usually psychological, or due to inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes), not the active drug. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor. It might be worth switching back - but it’s rarely because the drug doesn’t work.

The system works because it’s grounded in real data, not guesswork. Cmax and AUC aren’t just regulatory checkboxes. They’re the bridge between chemistry and clinical outcomes. They tell us, with scientific certainty, that a $5 generic pill will do the same job as a $50 brand-name one.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

While Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard, new tools are emerging. Modeling and simulation are being tested to predict bioequivalence without full clinical trials - especially for drugs with well-understood absorption patterns. The FDA’s 2023 roadmap suggests this could cut study times and costs in the future.

But for now, nothing replaces the real-world data. Over 120 countries use the same Cmax and AUC framework. It’s been validated across decades, millions of patients, and countless generic products. Even as science evolves, these two numbers will keep their place at the heart of drug safety and access.

Why do regulators require both Cmax and AUC instead of just one?

Cmax tells you how fast the drug reaches its highest level - important for drugs that need to act quickly or that cause side effects at high peaks. AUC tells you the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time - critical for drugs that work best with steady levels. Both are needed because a drug can have the same total exposure (AUC) but very different peak levels (Cmax), which can change how it works or how safe it is.

What does the 80%-125% range mean in practical terms?

It means the generic drug’s Cmax or AUC must be no less than 80% and no more than 125% of the brand-name drug’s value. For example, if the brand’s AUC is 100 mg·h/L, the generic’s must be between 80 and 125 mg·h/L. This 20% window is based on decades of data showing that differences smaller than this don’t affect how well the drug works or its safety for most medications.

Are there drugs that need tighter bioequivalence limits?

Yes. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and some anti-seizure medications - require stricter limits, often 90%-111%. Even small changes in exposure can lead to serious side effects or loss of effectiveness. Regulators apply these tighter rules only to these high-risk drugs because the margin for error is very small.

Why do some people feel different on a generic drug?

Most often, it’s not because the active ingredient is different. Generic drugs must contain the same active drug in the same amount. Differences in how you feel are usually due to inactive ingredients - like fillers, dyes, or coatings - which can affect how quickly the pill breaks down in your stomach. Some people are sensitive to these additives. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor before switching back.

Do bioequivalence studies prove that generics are as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes, but indirectly. Bioequivalence studies don’t test clinical outcomes like heart attacks or seizures. Instead, they prove the drug enters your bloodstream the same way. Since thousands of studies and real-world data show no difference in outcomes between bioequivalent generics and brands, regulators accept this as proof of safety and effectiveness. A 2019 analysis of 42 studies found no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy or safety.

14 Comments

Wow, this is actually one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read on bioequivalence. I’m a pharmacist and even I sometimes zone out when people start talking about AUC, but you made it feel like a story. Seriously, thank you. 🙌

Let’s be real - if you’re still skeptical about generics, you’re either getting paid by Big Pharma or you’ve never checked your own prescription receipt. I’ve been on generic warfarin for 8 years. My INR’s been stable as hell. Stop letting marketing scare you.

As someone who’s helped run bioequivalence studies in India, I can tell you - the process is brutal. We had to recruit 36 healthy volunteers, wake them up every hour for 72 hours, draw blood, and make sure they didn’t eat anything weird. And then the data gets analyzed with software that costs more than my car. But here’s the thing: if the numbers pass, it’s safe. Period. And yes, we’ve seen generics save lives in rural clinics where brand names are unaffordable. This isn’t just science - it’s justice.

Okay, so I read this whole thing because I was bored, but honestly? It’s still too much jargon. Like, I get that Cmax and AUC are numbers, but why can’t they just say ‘the generic has to be close enough’? Do we really need to know about log-normal distributions? Who even uses WinNonlin? I just want my pills to work without having to do a PhD in pharmacokinetics before breakfast. Also, why does everyone act like the FDA is some holy council? They approved Vioxx once, for crying out loud.

Life’s like a drug curve, man. Sometimes you peak fast, sometimes you linger. The body doesn’t care about brand names - it just wants consistency. 🌿💊

While the general exposition is commendable, I must point out that the assertion regarding the 80%-125% interval as a statistically derived threshold is, in fact, oversimplified. The interval was not derived from ‘statistical analysis’ alone, but through a consensus of regulatory bodies informed by clinical pharmacology studies conducted between 1978 and 1992. The log-transformation methodology, while mathematically elegant, remains contingent upon the assumption of multiplicative error structures - a condition not universally validated across all drug classes. One might reasonably argue that the current paradigm is ripe for revision in light of population pharmacokinetic modeling advances.

So you’re telling me that after all this, we’re still just guessing? I mean, they test on 36 healthy people - who probably don’t have diabetes, heart disease, or take 12 other meds - and then say ‘oh yeah, this works for everyone.’ What a joke. My uncle took a generic antidepressant and ended up in the psych ward. Coincidence? Or just the system ignoring real-world complexity? I’m not buying it.

Interesting. I’ve never thought about how blood draw timing affects Cmax. Do they ever use wearable sensors now? Or is it still all vials and needles?

Who cares about all this math when you can just buy the brand and be done with it. Generics are for people who can’t afford the real thing. The FDA doesn’t know what they’re doing. I’ve seen people crash on generics. End of story.

USA and Europe think they own the science but India and Africa have been making generics for decades without all this fancy testing. We don’t need your 80-125 rule. Our pills work just fine. Stop acting like you invented medicine

Okay so I read this and I’m like… wait… so if my generic blood pressure med has the same AUC but like… a lower Cmax… does that mean I might feel dizzy at first? Because I DO feel dizzy sometimes in the morning… and I switched to generic last year… and I’m like… maybe it’s not the coffee??

Let’s not romanticize this. The bioequivalence framework was designed to bypass clinical trials - not because it’s perfect, but because it’s cheap. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a corporate giveaway disguised as public policy. And now we have 1,200 approvals a year with zero long-term outcome data. That’s not science - that’s convenience.

Generics work. If you feel different, it’s not the drug. It’s your brain. Or the dye. Talk to your pharmacist.

I can’t believe people still believe this. The FDA is corrupt. Big Pharma owns them. You think they’d let a $5 pill be just as good as a $50 one? Please. Wake up.